The Duku Highway: A Corridor of East-West Communication

In the summer of 20XX I set off on a 561-kilometer journey along the Duku Highway — a road more often described as a “scenic drive” than a pathway into history. But to me this ride was never just about glaciers, grasslands or red-rock gorges. It was an expedition into the layered tapestry of Xinjiang’s past and present: a chance to pedal through ancient Silk Road memories, remote nomadic valleys, and centuries-old cultural crossroads.

What follows isn’t merely a travel log. This is a personal attempt to explore how geography and human stories intersect along one of China’s most dramatic mountain roads. I invite you to join me in witnessing how the sharp turn of a bike wheel can trace the faint footprints of history — and how, riding under Tianshan peaks and sleeping beneath starlit skies, one can hear the whispers of vanished caravans and the whispers of days long past.*

*note: this website is best viewed on laptop with full screen enabled

Day 1

The sun sharpened as my friend and I flew west. Its rays seemed to grow denser in the air, like a weight added onto warmth. Beneath the window, the land flattened into shades of copper and bone. Tracts and tracts of desert stretched out, stitched by thin, straight dirt roads that went nowhere visible. Between the dunes, faint greenish stains appeared, indicating oases and the remnants of dried-out riverbeds. Sometimes I saw grids marked on the sand, so precise they looked drawn by a ruler: irrigation, perhaps, or the lines of a geological survey. Human order sketched onto the silence of nature.

Ürümqi Diwopu (Tianshan) International Airport

1

_edited.jpg)

On the ground, the air felt thinner and clearer (and dryer, very dry). We hurried through the terminal and onto the bus that would take us to Dushanzi. As the city thinned behind us, the road unwound toward the west. I had expected a dry, harsh landscape, but the world outside the window kept contradicting me. The fields were lush; the air carried the smell of grass and dust. Rows of trees lined the road like sentinels, and beyond them, the land stretched endlessly, an oscillation between fertility and desert.

The bus passed clusters of houses, small towns where people sat outside under vines, drinking tea in the long light. We watched in silence. It was early evening by the clock, but the sun still hung high, the western hour stretched by geography. Xinjiang, despite being more than 3000 kilometres west of Beijing, still uses Beijing Time. By the time we reached Dushanzi, the light had mellowed into gold. The town felt quiet, almost self-contained. It was a place that knew how to wait.At the cyclists’ hostel, rows of bikes leaned against the wall, ready and expectant. The air smelled faintly of oil and wind. The owner spoke little but smiled often, constantly tending to the needs of passing cyclists, who all sat down in front of a tea table to chat. All seemed to hum with potential.

Tomorrow, we begin.

Day 2

Morning light came early, filling the streets with a dry brilliance. We walked to the Duku Highway Museum, a low modern building set against the endless blue of the sky above the expanse of desert just outside the town. Inside, the air was cool and faintly metallic. On the walls, yellowed photographs showed men with shovels and pickaxes, their faces burned by wind and sun. Machines looked primitive, almost improvised. It was hard to imagine these people, decades ago, building a road across such mountains.

Outside, where they possibly once camped in mud, stood a polished plaza and a slab of stone marking “Duku Highway, 0 km.” Bikers, campers, and road-trippers gathered around it, posing for photos before setting off.

In the afternoon, we finally joined them as we decided to scout ahead before the long haul. The road out of town began gently, then rose without warning. The heat pressed down; the air was still. Cars swept past, each gust a slap of dust and wind. My legs began to burn, and by the fifth kilometre, even sitting hurt. The first part of the highway was straight as an arrow, and we could see the ripples of heated air rising from the asphalt. Funnily enough, amid the dunes, there were patches of shrubbery and houses with billboards that advertised skiing opportunities. It was difficult to imagine that this scalding wilderness could, in the colder months, hold snow deep enough to ski on.

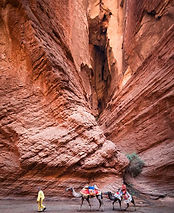

When we reached the Dushanzi Grand Canyon, I was expecting anything but the great gorge laid bare before me. I split open like the earth had been torn by hand, walls of grey rock running for miles, moulded by millennia of rainfall and river water.

Yet on the cliffs, metres away from a drop of a hundred metres, a different world had risen: ticket booths, snack stalls, and even a small roller coaster that traced the edge of the canyon. This meeting of grandeur and leisure, of erosion and entertainment, was peculiar, one would almost be bound to ask, are the tourists here to admire a canyon, or just to take a ride down the little roller coaster, take a selfie, and post “I was here!” on their social media accounts?

We rode back as the sun tilted west, our shadows stretching long over the road. By evening, we met the rest of our team: three new faces, each equally sunburned and smiling. Over dinner, we talked about climbs and distances, and the improbable road ahead. My body ached, but the thought of the days to come kept me awake long after the town had gone quiet.

Day 3

The first kilometres were smooth, almost too smooth. The asphalt shimmered like glass under the morning sun, and the city receded without protest. The noise of engines dulled behind us until all that remained was the thin hum of rubber against road. We pedalled easily, our shadows stretching long and clear. The Duku Highway lay ahead, empty yet strangely inviting. I felt a lightness then, a sort of reckless energy.

We stopped at a roadside stall where a woman in a floral headscarf sold watermelon. The fruit was cool and sweet, the kind that seems to rinse the dust off your tongue. I ate three slices before setting off again. My legs felt fresh. I was the youngest on the team, and for the first few stretches, it showed. I rode ahead, cutting through the road alone, convinced that strength was momentum. I didn’t realise how much I was spending to feel that freedom.

Very soon, the road began to rise. Not abruptly, but with a steady insistence, like an upward whisper that tightened into a strain. The grass dried into yellow patches, and the wind changed its sound. I passed a sign that said “Come Back Soon,” and it struck me that we were leaving the world of towns and people behind. The scent of asphalt gave way to that of dust and sunburnt grass. Beyond the last row of trees, the Tianshan Mountains

began to gather on the horizon, a

shadow that grew larger with

each turn of the pedal.

The climb was not steep, but it was endless. The kind that wears you down not by difficulty, but by duration. The sun sat directly above us, bright and cruel. There was nowhere to hide from it. The road wound between pastures where sheep and cattle grazed lazily, their wool faintly golden in the light. Their bleats carried across the wind, soft but persistent. Were they welcoming us to their domain, or just complaining that? the grass was too dry? In my fatigue, I tried imagining that it was the former, as I pushed down on the pedals and kept on moving forward.

We stopped at a rest point before the next ascent. Owing to another highway which intersected the Duku Highway here, this was a well-developed and busy place.. Tourists milled about with cameras, their cars lined up neatly by the curb. I walked to the tap beside the bathroom and poured water over my head until I was soaked. The shock of cold was electric. For a moment, as the water drenched me, all feeling of fatigue disappeared as I revelled in the chilliness, fully aware, though, that in five minutes all the water would dry out in the heat.

A while later, we began climbing again, but thankfully soon came to the ridge. The road seemed to tilt against the sky. When I finally looked back, the valley lay open and shimmering. Fields, roads, and rivers flattened into a pattern of light. The flocks of sheep and cattle below looked like tiny clouds drifting across the earth. I stood straddling my bike, breath heavy, trying to take it all in. The silence was immense.

The beauty was so enveloping that I was shocked that we had already come to the top of the mountain. The slope suddenly broke open, and the road unfurled like a ribbon. We began descending. The wind caught my face and roared in my ears. I barely touched the pedals; gravity did the work. The world blurred, as curves, cliffs, and the flash of a truck mirror all flashed by. On one side, stone walls; on the other, a drop that fell away into a wash of blue and yellow haze. White-pebbled viewing platforms appeared along the edge, tourists leaning over to capture the view. I felt as though I was flying, and for a few minutes, the exhaustion was replaced by pure exhilaration.

At the bottom of the valley, we stopped for lunch. A small restaurant stood alone by the road, its door open, flashing with new blue paint, the smell of oil and spice drifting out. Inside, the walls were bare except for a calendar and a picture of a lake. At the far end, a staircase led up, presumably to the bedrooms. Outside was a makeshift convenience shop, with shelves and refrigerators set up under a tin roof. A whole lamb carcass hung from a hook by the entrance, fresh and glistening with blood and fat. We ate shou zhua fan—rice, carrots, and lamb. The rice was soft, the meat tender and fatty. Afterwards, I lay in our support van, half-asleep, listening to the sound of conversation fading into the hum of the wind outside.

The afternoon was another story. The road climbed again, harder this time. The mountains closed in, and cliffs loomed over us like walls. The wind picked up, pushing against our wheels. The ground grew rocky, and loose stones clattered under our tyres. At a place locals called the Tiger’s Mouth, the danger was obvious. Boulders were scattered across the road; guardrails bent from fallen rock. Below, the river churned as milky water swirling over jagged stone, foaming into the gorge. The wind was ever more unforgiving, as the mountains and rocks funnelled torrents of gust into the valley and onto the roads. I had to get off the bike and push many times that afternoon.

Yet for the first time on this trip, passengers, especially children, poked their heads out from passing vehicles and cheered us on. We met a group of locals, nomads, riding their horses with their children upon this stretch of road. How interesting, I thought, that horses shared the road with bicycles, huge lorries, camper vans, and stage wagons. A balance of tradition and modernity, and, somehow, bikes seemed like the perfect blend of the two. Later, we even met an old shepherd who was resting next to the road with his horse and dogs. He was also a part of the local ecological conservation group, and the gap and tiny platform beside the road, along with a few signs, was the entirety of his station.

As the day leaned toward evening, the sun sank low, and colours eventually turned metallic. My hands were sore despite my gloves, my legs were weak, and my bottom ached. The temperature fell quickly. I pulled on my vest as we descended into the next valley. There, at last, stood our hostel, tucked into the slope and boulders like a house that had grown out of the earth.The owners greeted us with brisk kindness. They were mountain people, weathered and straightforward, a little impatient at times, perhaps, but it was always for the purpose of hospitality. The man smiled with his eyes more than his mouth; the woman moved quickly, already preparing food. Dinner was lamb noodles, thick and chewy, slick with chilli oil. The smell filled the room, mixing with woodsmoke and cold air. I ate like I never ate before.Later, at night, I stepped outside. The stars were fierce, thousands of them, like dust scattered on black glass. The night air stung my face. Somewhere not far in the dark, water rushed over stone. I felt the ache in my legs, and the salt from sweat dried on my skin.

Seventy-eight kilometres. The first mountain day. The hardest thing I had done so far, and yet, standing there in the silence, I felt only calm. The uncertainty that had shadowed me before seemed smaller now, like the city lights I had left behind. The road ahead was long, but it was real, and I was already on it.

Day 4

I woke to a cold that bit through fabric. The mountains do not wake gently; their moods change faster than light. I pulled on my cycling gear, still half-asleep, only to hear that the road ahead was closed. Rain overnight, they said. Falling rocks. So we waited. Morning stretched into noon, and anxiety pressed against my ribs. We had to complete the route within eight days, otherwise, we would miss our return trips in Kuqa. The others played cards or stared at the fog. I wandered outside. The valley where our hostel stood was enormous. Grey cliffs rose on both sides, slashed with green ferns and moss. The air smelled faintly of wet stone. Across the road, white rapids tumbled through a turquoise channel, winding down toward somewhere unseen. To the north and south, the valley opened up to reveal a striking blue sky, a few wisps of cloud floating gently by.

By afternoon, the news came: the road was open again, but the climb was too long—five per cent average incline, eleven at the steepest. It would have taken us three to four hours. So we decided to go by van to the summit and descend from there. I nodded, hesitating, yet finally agreeing. In reality, I felt cheated,

as if the mountain had refused to meet me on its own terms.The ascent by van took an hour. Out the window, waterfalls stitched the cliffs, as snow mixed with rain tumbled down, the world half grey, half white. We passed an old tunnel, its walls flaking, dark as a throat. No lights, no signs. Only the sound of tyres on stone.Then, suddenly, the top. The world opened. The air was thin, sharp enough to taste. As we began to descend, this time on a bike, rock turned to soil, snow to grass. No trees yet, but green lines appeared, winding down the slopes. Sheep and cattle dotted the fields. In the distance, small white yurts stood like scattered shells.

At a turn in the road, as we rested, I met a Kazakh woman. She emerged from her yurt, her voice soft and deliberate, asking whether the road was still closed. Her Mandarin was halting, her tone careful. Inside her home, I saw narrow beds, a small stove with a pot simmering, and a pickup truck parked outside. Tradition and modernity, side by side. There was no ceremony in the coexistence, just life.Further down, a lone bulldozer cleared fallen boulders from the road. The driver waved as we passed, and I wondered how long he had been there, moving stones that kept returning. The descent was beautiful, too beautiful, almost. The slope carried us without effort, but the joy was hollow. Without the climb, the rush of air meant less. Strangely enough, simply descending without the huffing and puffing when we came up the mountain did not feel quite right.

As we reached the bottom, the mountains softened into open grassland. Horses grazed in the distance, their shapes blurred by light. A young man, perhaps home from university to help with the family during the summer holidays, ran up from a nearby fence and asked if we wanted to ride. We smiled and shook our heads. We had no time. He laughed and chased his horse

back into the field.Soon, signs of life multiplied: fences, smoke, the faint shape of houses.Very soon, we came to the foot of the mountains and the entrance to Qiaoerma. The day’s journey had been short and easy. YetI felt oddly restless. Maybe the satisfaction of descending dependson the memory of struggle. Without the climb, even beauty feelsborrowed. The road had given us everything except the chanceto earn it. Meanwhile, I also felt the harshness and majestyof nature. Here, human will was dictated by unforeseeablechanges; so many tourists had had their plans dashedsimply because of the rain or the wind.

Day 5

We left the hostel in the morning light, twenty kilometres from the Duku Highway, our wheels humming over the smooth road that wound through the Tangbula grasslands. The air was cool, the wind gentle. Though it was still summertime, it seemed that spring had gathered itself fully here instead: green stretched unbroken to the mountains, interrupted only by pink and violet flowers and the tall silhouettes of spruce. The Kush River followed beside us, clear and restless, breaking over white rocks. In the meadows, yurts stood close to the banks. Sheep, cattle, and horses shared the same water, heads bent as though in prayer. The mountains on either side were mild, not towering yet solemn, their slopes softened by grass and shadow.'

By noon, we reached Qiao’erma, where the river bent wide and the road paused. After lunch, the climb began again. It seemed a routine was forming; a climb was always expected, always feared at the beginning, yet when the descent finally came, all that negativity washed away. The valley narrowed, and the road pressed closer to the river. Spruce trees grew denser, their scent sharper, mingling with damp soil. It was the kind of forest that seemed to hum quietly when you stopped to listen. Still, the incline was steady. Here, the river gushed across rocks and pebbles, tinkling and glistening in the sun.After an hour, the valley closed in completely. The road crossed the Kush River and turned sharply upward. Clouds gathered over a tall ridge in the far distance. The warmth dissolved; wind returned with a chill that felt personal. Grass gave way to black stone, slick from earlier rain. My breath grew shallow. Every pedal stroke was a negotiation. When the slope steepened further, I dismounted and pushed, shoes grinding against gravel, my thoughts narrowed to a single rhythm: one more step. Discomfort had more of a say here than fatigue. My legs burned, my stomach cramped, and the urgent need for a bathroom mocked every turn.

But the road, patient as stone, finally gave up its height. I reached the top suddenly. Perhaps it was my constant yet unsuccessful search for a roadside bathroom on the way up that took my mind off how far I had actually gotten. I rushed to the bathroom at the rest stop, and the simple relief felt like victory. After resting, we gathered by the tunnel that cut through the mountain. The walls were rough and wet, the light weak. Inside, our voices echoed like hollow bells. Emerging on the far side, we met a small group of foreign cyclists. Their faces were flushed, their gear worn, all of us laughing in that unspoken way travellers recognise each other. We were united by the same road, the same fatigue, the same stubborn love for open air and steep climbs.Then came the descent. We stopped first at a cliff to take in the view and saw, below the guardrail, heaps of plastic bottles and plastic bags. The garbage clung to the slope like a rash. Beauty and neglect side by side; it was hard to know which to look at.We began to descend, and the mountain began to change again. Red cliffs rose around us, cut by sudden sunlight. A brief rain fell, fine and slanted, and a rainbow arched over the valley. The road twisted downward in wide curves. I leaned into each turn, gravity taking command. We averaged thirty-seven kilometres per hour going down. At the bottom of the valley, the light grew soft again. The road straightened, leading us toward Nalati Town. By the time we arrived, the sun was setting directly down one of the streets, the light pooling on the pavement like honey. The mountains behind us were already fading to blue.

Day 6

The road began gently,

cutting through forests still wet

with morning dew. For a while, it

was smooth before the incline began to

show itself, subtle at first, then more

insistent as we started the climb

toward the Bayinbuluke Grasslands.

Ahead rose Yeersikeqi Mountain, and

beyond it, the Laerdun Pass, our

doorway to the grasslands of

the plateau. Surprisingly, I felt

strong. Perhaps I was finally

learning the rhythm of ascent.The

road coiled around the slopes in long silver curves.

By noon, we reached the top. It was the lowest mountain pass of the journey, though it didn’t feel like a summit, more like a quiet threshold. At the crest, a motorcyclist appeared out of the glare, all in black. His visor hid his face, but as he passed, he raised a thumb. I

returned it instinctively, and for a brief second the road was

just a thin thread connecting two travelers moving in opposite directions.The descent never really came. The

mountain simply opened into grass. Rock and trees faded

into a vast green sheet. This was Bayinbuluke, the heart of

the plateau. Grass stretched to every horizon, broken only by

dots of white and brown: yurts, cattle, sheep. Clouds drifted above, their shadows gliding over the plain like slow ships. Sunlight spilt through in straight beams, turning patches of grass shining and silver.

We stopped for lunch beside the road. A horse stood nearby, fitted with cardboard wings for tourists, like a ridiculous Pegasus against the immensity of the steppe. It made me laugh; the mountains rarely offered humour, and I was grateful for it.The afternoon was easy. The road levelled, sometimes even tilted downward. We rode fast, the wind trailing behind us, until by five o’clock we reached Bayinbuluke Town. This was the first time we had made good time, and for good reason. Tomorrow promised the longest ride of all, 156 kilometres. We needed our rest tonight.

Day 7

The morning began before the heat, when the light was still pale and the air sharp enough to sting the throat. 156 kilometres lay ahead, an absurd number I half believed I couldn’t manage. But I started anyway, for what else could I do?

Soon, we passed a small airport. It had one runway, a tiny terminal, and a control tower that seemed too clean for this wind-scoured plateau. Modernity looked almost embarrassed out here. No drones allowed, which meant the sky would keep its secrets today.

Shops at Rest Stops

15

Two cyclists appeared on the road

ahead, both older men, retired, their

panniers heavy with supplies. They

said they were from Hebei, crossing

the country on their own. Their clothes

were faded, their wheels clattered, but

they moved quickly, steadily, and

unshakably. I envied their ease. As the

road levelled, we sped too, gliding at

thirty kilometres an hour, the air thin but

bearable.

A pond appeared by the roadside, a perfect

mirror of the sky, so clear that the boundary

between water and cloud dissolved. We

stopped for photos. Then, about forty

kilometres in, the road curved south. The grass

began to glow purple. Wild lavender was in

bloom. Fields rolled in waves of violet and

green, the colour breaking only for sheep and

parked cars. The closer we drew to the

mountains, the more the palette deepened.

Purple grass, green slopes, grey rock, and snow

white peaks coalesced all under the impossible

blue.

By noon, we reached the southern edge of the

grassland, where the hills began. Lunch was fresh

noodles. Another cyclist sat across from us, and by

coincidence, he was from my own city. We laughed

about it: two travellers meeting at a roadside shack,

halfway up the spine of the Tianshan.Afternoon

came dark and heavy. Clouds swallowed the light;

rain began as a whisper and then turned fierce.

We hid in the van while the storm passed. When

it eased, the sky broke open. Droplets caught

the sunlight and hung like jewels in the air,

gold against the grey. We started climbing

again.The slope rose into cliffs of wet stone

and low ferns, like the first day of the

journey replayed in harsher colours. Old

bridges lay crumbling beside the new

asphalt road. The stone slabs were split

by time, their edges smoothed by

wheels and water. Ahead stood the

tunnel, a black mouth cut into the

ridge. Two cyclists emerged

from the other side,

shouting a warning: “

Two kilometres long

—ride safe!”

At the top, our van waited beside a stone police post with a red roof, nestled among the rocks. Two officers stepped out, amused

by the sight of us. One said, half sternly, that the descent was too steep and we weren’t allowed to ride down. Then he grinned and offered to “lock my wheels for safety.” When I hesitated, he burst into laughter. It was a joke, of course. Up here, at nearly three thousand meters, humour was a way to keep the wind from feeling too chilly. Their station was little more than a place to hide out from the wind and rain, with only the most basic appliances. They had no neighbours, no trees, only the mountain and the road. They talked to travellers to pass the time.

When the rest of our team arrived, we repeated the joke, pretending to forbid them from descending. Everyone laughed. The climb’s exhaustion vanished in that shared absurdity. One officer noticed my bare red legs, almost numb from the icy wind, and my heavy windbreaker, laughed again, and said I was dressed like two different seasons at once.

We had to be on our way, though, and bid them farewell. The descent was steep, the road slick from rain. Every turn demanded care; my fingers ached from braking. The mountains shifted colour as we dropped from grey to brown, then suddenly red. Danxia country. The slopes were striped with layers of iron and clay, carved by water into soft ridges.At the foot of the range, the road levelled into a sequence of small basins, and the Longchi lakes appeared, one large, one small. The water was turquoise, edged with ferns, so still it seemed unreal. From there, a final series of hills led us toward Kuqa. The wind rose again, fierce and playful, at times almost enough to topple the bike.

Near the last tunnel, my sunglasses flew off. I panicked, but my friend behind me caught them before they hit the ground. It felt symbolic somehow, how often someone else sees what you drop in motion.By the time we reached the hostel, night had already fallen. Dinner came late, at nine. My body buzzed with fatigue and disbelief. One hundred and fifty-six kilometres. I had done it. The longest day, and the first time I truly felt I had crossed something; the distance, of course, but also the thin line between fear and endurance.

Day 8

The last day began in the rain. We cycled through the Danxia

rocks, the world around us a deep red made darker by the storm.

The rain didn’t relent, and neither did we. It was, somehow,

harder than the 156 kilometres the day before. There was more

rain, more trucks, more coal. Enormous lorries rumbled past, their

loads spilling dark dust onto the road. When they passed too close,

waves of coal water swept over us, soaking everything. My leggings

clung to my legs, gritty with pebbles of coal. Even my waterproof jacket was dripping black water, and the spray from my wheels flecked my

back, my helmet, my hair. For days afterwards, I’d still find specks of coal tangled there.

But even then, there was beauty. The rain ran down the red rock faces like molten glass, red and heavy with the soil, washing the landscape clean, making everything burn with colour. Somewhere along the way, we passed the 1000 km marker (the road began in Altay, 500 kilometres or so north of where we had begun). My glasses were smeared with dust and water, my hands blackened from wiping them clean.

By midday, we reached the Kuqa Mysterious Canyon, where I’d imagined resting and, exploring, but we were disappointed to find that the rain had closed it off. Somehow that small disappointment made the cold feel sharper, the wet heavier. I stopped cycling. I told myself it was for safety, and later I would be grateful for that decision. We ate lamb skewers in the diner nearby, the meat hot and smoky against the chill air. After lunch, I changed into dry clothes and felt human again.

An hour later, as we got going on the final stretch to Kuqa, the

van caught up with one of our teammates. His bike was on the

ground, and he sat beside it, bleeding. Blood was streaking

down his hands and face. He had slipped on the wet

road, skinned his palms raw, and cracked a few

teeth. What was worse was that he was covered

from head to toe in coal dust, some even

mixing into his wounds. It was the first time

I understood, fully, how dangerous all this

could be. These roads were unkind to those

who failed to give them the dignity they

deserved. We helped him into the van and

drove toward our final destination, where

someone from Kuqa would rendezvous and

bring him to a hospital.

By evening, the rain had thinned to mist. We reached the end of the Duku Highway. There was a mural there, and we took our photos like everyone else. The act seemed insignificant. The road behind us, the miles of wind and coal and rain, and the people who’d stared in disbelief when they learned we’d come all the way from Dushanzi, that was what stuck with me. Here too, their eyes said the same thing: surprise, approval, something close to respect. We stood before the mural, faces dark with dust, exhausted but happy. The highway had ended, but in that quiet, dirty, rain-washed place, it only just felt like something had begun.

A half-hour later, we arrived at Kuqa, an idyllic little town situated on the outskirts of the massive Taklamakan Desert. We stopped at the cyclists’ hostel and bid farewell to our teammates. It all felt so rushed; seven days of climbing the hills together, yet everything just ended in an instant. Soon after, our team leader had already packed up a few spare bikes to take back to Dushanzi for the next group of cyclists – a 13-hour car drive back the way we had come seven days before. We took a while to pack, as we would be taking the train to Kush, which was further west. In the meantime, we took stock of our surroundings and wandered around the old city section of Kuqa. The only thing of note was the colourful decorations around the place. Doors, windows, leaflets hanging outside: all were painted with various shades of colour, twisting and intertwining with each other. It was a most exotic sight. Looking beyond the colourful doors and windows, you could see the residents of Kuqa at home, picking beans and sorting vegetables. Apart from the bazaar in the middle of town, the whole city was tranquil and had a pastoral feeling. As you sat on the front porch of a café and enjoyed the sunset, the wind would go by gently, offering a strange, untethered feeling.

Our journey closed where another would one day begin. The map, once abstract lines and names, had become memory, with each turn of the wheel a sentence, each climb a pause. The Duku Highway didn’t lead me anywhere new; it led me back to the reason people travel at all: to see, to endure, to remember.

.jpg)